- 01.Weight problem of solar cells in HAPS

- 02.Comparison of general solar cells and solar cells for HAPS

- 03.Design and development points to achieve goals

- 04.High technology to realize ultra-light weight and high efficiency

- 05.Weight and efficiency

- 06.Achieved a module weight of 600 g/m² or less

- 07.Perovskite/Silicon Tandem Solar Cells

- 08.Tackling the Modularization of Perovskite/Silicon Tandem Solar Cells

- 09.Can perovskite, which is highly susceptible to moisture, be protected using materials other than glass?

- 10.Practical application of ultra-lightweight tandem modules and expansion plan for HAPS

- Blog

- HAPS

【Updated Aug 1, 2025】The Challenge of Ultra-Lightweight Solar Modules for HAPS

#HAPS #SolarModules

Aug 01, 2025

SoftBank Corp.

Topics

1. Weight problem of solar cells in HAPS

(Click here for an explanation of HAPS)

One of SoftBank’s advanced initiatives is the development of High Altitude Platform Station (HAPS), a ”flying base station” that operates in the stratosphere at an altitude of 20 km. Since the stratosphere experiences minimal environmental fluctuations, the energy (demand) required for flight remains almost constant. In contrast, the energy (supply) from solar cells depends on solar radiation, which varies with the season and geographical location.

(Click here for an explanation of the HAPS energy balance)

Since HAPS operates without landing and must rely solely on the energy it generates itself, solar cells are installed across nearly every surface of the aircraft. For large airframes, the number of solar cell modules can reach several thousand, so even a slight increase in the weight of a single solar cell module can have a significant impact on flight performance. In fact, for such aircraft, a weight increase of just 100 g/m² can reduce the flightable latitude range by nearly 2 degrees. As a result, reducing the weight of solar cell modules has become a critical design issue.

2. Comparison of general solar cells and solar cells for HAPS

Typical solar cells installed on the ground or rooftops are protected by glass or metal frames and weigh 11 to 17 kg/m². Lightweight modules with thinner glass weigh 6.5 to 8.0 kg/m², and ultra-lightweight flexible modules, which replace glass with resin and omit the frame, weigh around 3.0 to 4.7 kg/m². On the other hand, the weight required for HAPS is 0.3 to 0.6 kg/m². This means the weight must be further reduced by an additional order of magnitude from even the ultra-lightweight ground-based modules. (Table 1)

Table 1. Weight comparison of solar cell modules

For this reason, SoftBank’s solar module development project for HAPS has identified weight reduction as one of its key objectives. The initial target for module weight was set at less than 700 g/m². This value was chosen because the ultra-lightweight crystalline silicon modules used in solar car races and similar applications typically weigh around 800 to 1000 g/m², and the first goal was to go below that threshold.

3. Design and development points to achieve goals

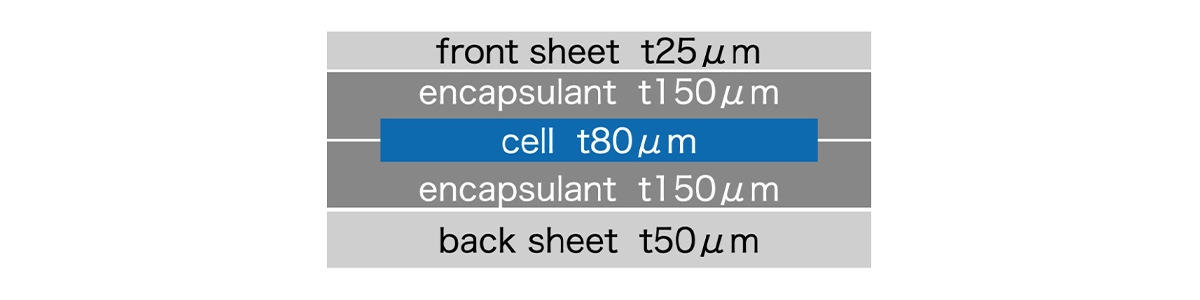

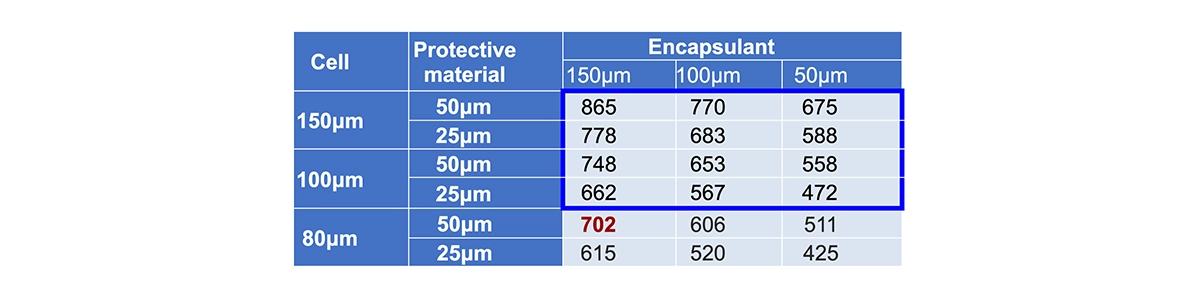

The results of the initial simulation on module weight are shown in Table 2. Based on trial estimates using various material types and thicknesses, it was calculated that the total weight would reach approximately 700 g/m² when the cell thickness is 80 µm, the encapsulant material thickness is 150 µm, and the protective material thickness is 50 µm.

Table 2. Weight estimation of lightweight module (g/m²)

Selection of solar cells:

The lightest and most efficient solar cells currently available are the compound solar cells for space applications; however, they are expensive and require a long manufacturing period. For this reason, we limited our selection to high-efficiency crystalline silicon cells, which are available at approximately 1/1000 the cost. With the cooperation of a solar cell manufacturer, we aimed to develop the thinnest, lightest, and most efficient cell among those of practical size that can currently be produced.

Selection of components:

For the front and back protective layers, we used ultra-thin, weather-resistant resin. For series connections between cells and lamination, we used the thinnest possible wiring components and ultra-thin encapsulant materials. Since the operating environment, weight requirements, and cost requirements differ significantly from those of solar cells for terrestrial applications, we broadly considered a wide range of options, including high-performance components that are not normally used.

4. High technology to realize ultra-light weight and high efficiency

The solar cells were developed by LONGi (Head office: Xi’an, China), the world’s largest solar cell manufacturer. The modularization technology was developed in collaboration with Fujipream Corporation (Head office: Himeji City, Hyogo Prefecture), a company specializing in lightweight solar modules. This project was carried out through a three-party collaboration involving SoftBank, LONGi, and Fujipream.

Ultra-thin SHJ (Silicon Hetero Junction) cell

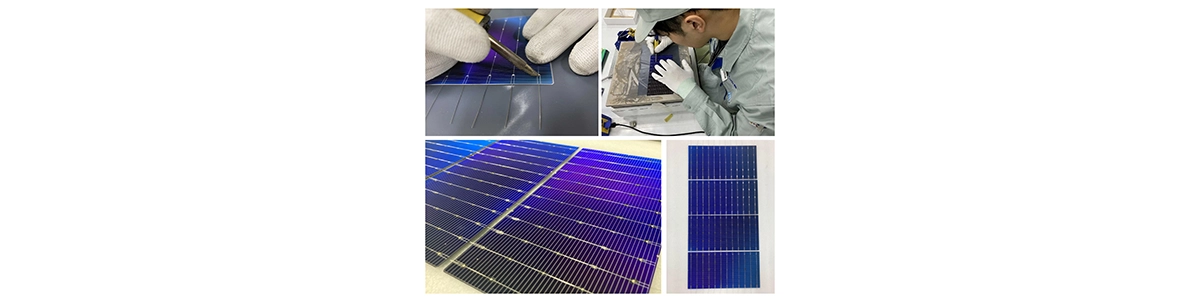

The cell used in this project is an ultra-lightweight SHJ (Silicon Hetero Junction) cell of 182mm × 91mm with a cell thickness of 80µm (about half the thickness of a cell installed for the ground generally) developed by LONGi (Figure 1). In November 2022, LONGi achieved a world-record efficiency of 26.81% for silicon solar cells using SHJ technology. The 80 µm-thick cell used in this project adopts the same technology as that record-setting cell and achieves an efficiency of over 25%, despites its reduced thickness and compact size. Generally, as silicon solar cells become thinner, light absorption decreases and efficiency declines. However, this trade-off has been overcome through advanced technology, making this one of the most outstanding solar cell products currently available.

Figure 1. Appearance of ultra-thin SHJ (Silicon Hetero Junction) cell

Development of ultra-lightweight modularization technology

Fujipream Co., Ltd. has been engaged in the development and production of complex large-screen flat displays and lightweight modules for terrestrial applications, utilizing its expertise in precision lamination technology. In this project, the company applied its technology and know-how to develop modularization technology for ultra-lightweight modules for HAPS.

For the series connection between cells, thin copper wire with a diameter of 250 µm was selected and soldered using low-melting-point solder (Figure 2). Since the manufacturing equipment was not compatible with the cells and wires used in this project, the process was carried out manually by skilled technicians.

Figure 2. Connection of ultrafine wires with low-melting-point solder

For the thickness of components other than the cell, we used 25 µm for the surface protective material, 150 µm for the encapsulant, which is about 1/4 the thickness of general ground products, and 50 µm for the back surface protective material (Figure 3). The combined thickness of urface protective material and encapsulant is 175 µm, which is thinner than the 250 µm diameter of wiring. Therefore, in order to laminate without gaps, the layers must conform precisely to the uneven surface created by the wires and other elements In particular, the 25 µm-thick surface protective material is extremely sensitive, and even a slight deviation in the lamination conditions can result in wrinkling and peeling as shown in Figure 4—this poses a critical risk of damage to the ultra-thin 80 µm cells. We focused on identifying lamination conditions that would enable gap-free integration under these demanding circumstances.

Figure 3. Protective material and encapsulant lamination

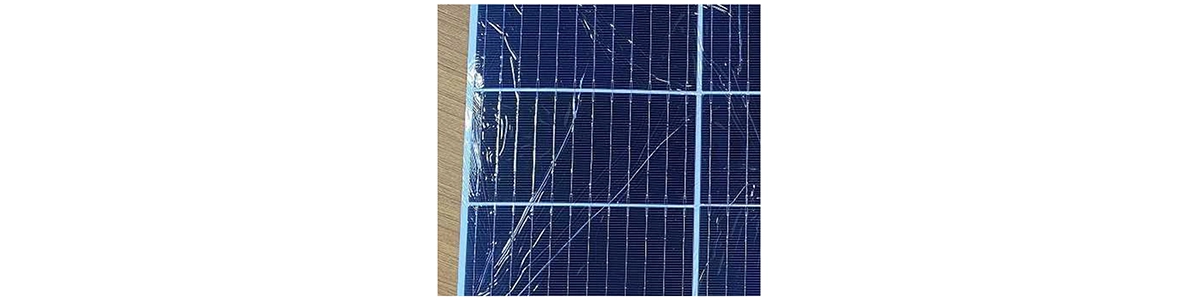

Figure 4. Wrinkled module

5. Weight and efficiency

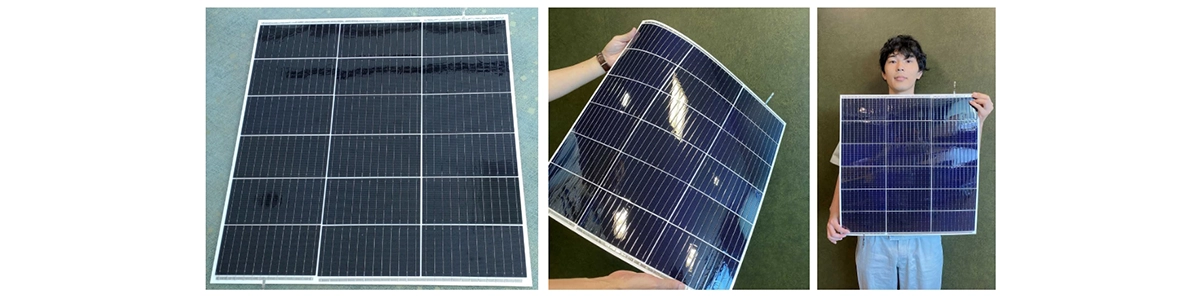

Figure 5. Appearance of ultra-lightweight solar module

Figure 5 shows the completed ultra-light solar module. The module measures 563 mm * 584mm and weighs 218.5 g. Based on these values, the unit weight is calculated as 665 g/m², successfully achieving the project target of less than 700 g/m². This level of lightness is considered among the best in the world for silicon solar modules.

In addition, by optimizing conditions such as cell layout and processing temperature during modularization, we achieved a uniform, high-quality finish with no wrinkles or peeling.

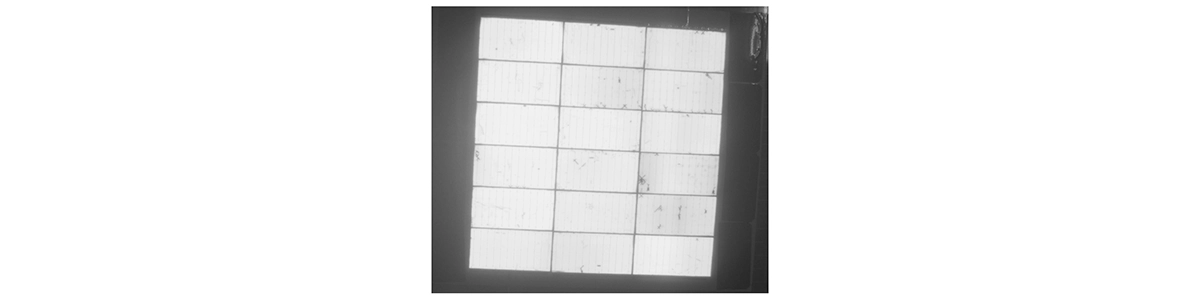

We also performed EL (Electroluminescence) testing to detect any invisible damage. As shown in Figure 6, no cracks in the cells or delamination of the wiring were observed.

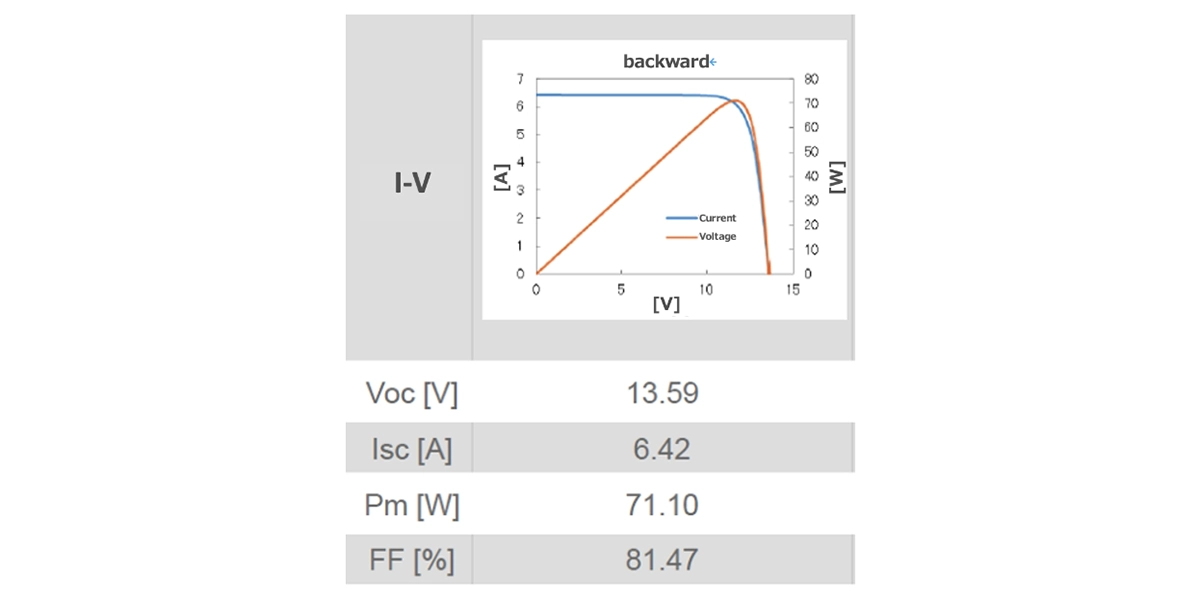

As for module performance, an output power (Pmax) of 71.1 W was recorded in the I–V measurement under AM 1.5 conditions (Figure 7). Given the effective area of the module—563 mm × 568 mm (with 2 mm cell spacing and 6 mm edge clearance)—this corresponds to an effective module efficiency of 22.2%.

Thus, the module not only met the target weight of less than 700 g/m², but also achieved world-class efficiency among ultra-lightweight silicon solar cell modules.

Figure 6. EL measurement results

Figure 7. I-V measurement test results (AM1.5)

6. Achieved a module weight of 600 g/m² or less

*The following content is based on results and data as of March 2024.

In the first phase of ultra-lightweight module prototyping, we achieved a weight of 665 g/m². This was a significant milestone, as it allowed us to gain extensive know-how on weight reduction. However, this result was largely attributed to the use of cutting-edge, ultra-lightweight cells supplied by LONGi’s research institute. Although these special-specification cells were advantageous in meeting the weight target, they were also rare and expensive, making them unsuitable for high-risk experimental processes due to the potential for damage.

Therefore, in the second phase, we adopted low-cost, ground-use cells that can be procured in large quantities by Fujipream Co., Ltd., and instead focused on comprehensively verifying lightweighting elements other than the cells.

Table 3. Estimated weight of lightweight modules (g/m²) *Red text: Phase 1, blue frame: Phase 2 evaluation range

In Phase 1, the cell thickness was 80 µm, but in this phase, all cells used were 100 µm or thicker. The most cost-effective and readily available cells had a thickness of 140 µm. Although this was disadvantageous for lightweight design, we prioritized cost efficiency and the ability to test a wide range of design approaches.

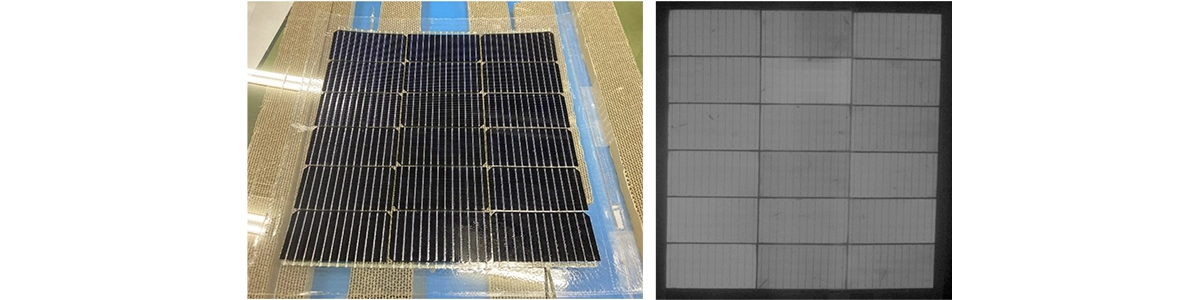

As a result, we comprehensively evaluated the areas marked in blue in Table 3, and ultimately achieved a module weight of 598.9 g/m² (with a cell thickness of 140 µm and module dimensions of 540 mm × 560 mm).

Figure 7 shows the appearance and EL (Electroluminescence) measurement images of the ultra-lightweight solar module prototyped in this phase.

Despite the significant handicap of increasing the cell thickness from 80 µm to 140 µm—a more than 70% increase—we succeeded in reducing the total module weight by over 10% compared to the first phase.

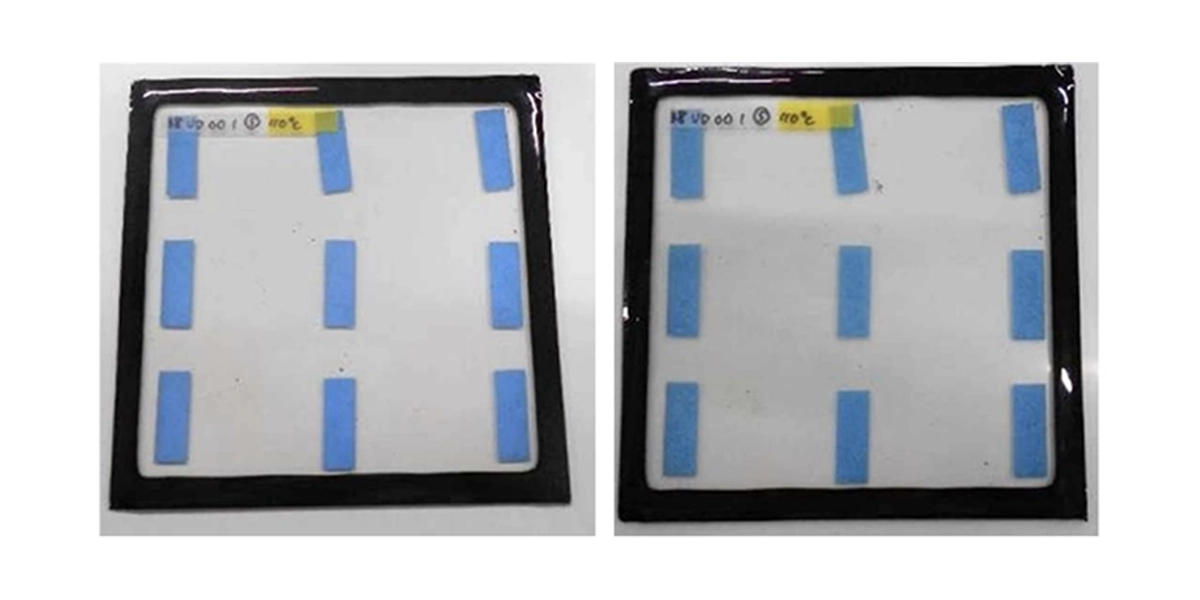

Figure 7. Appearance of ultra-lightweight solar module and EL measurement image

Figure 8. Differences in module structure between the previous and current versions

The main improvement in this phase was the tab (black portion in Figure 8) that collects current from the cell surface. The tab, or ribbon, is a metal conductor that carries the current gathered by the finger electrodes. If the tab height exceeds the thickness of the encapsulant, the resulting surface unevenness can cause wrinkles and bubbles during lamination, leading to potential cell damage.

While thinning the tabs helps reduce unevenness, making them too thin increases electrical resistance and reduces power output. Therefore, it is crucial to determine the thinnest possible tab dimension that does not degrade electrical performance.

We evaluated a wide range of configurations, including different tab cross-sectional shapes (round, flat, trapezoidal), connection methods (soldering, conductive adhesive), and types of sheet materials for encapsulation and protection.

SoftBank worked with research institutions and companies both in Japan and abroad to procure materials ranging from commercially available products to prototype-stage advanced materials. With Fujipream Co., Ltd. providing precision lamination technology and equipment, we were able to test unprecedented combinations of materials and fabrication methods.

As a result, we established a lamination process that achieves high quality even with 140 µm-thick cells, using just a 25 µm protective layer and a 100 µm encapsulant.

In this phase, we prioritized weight reduction over efficiency, so the module’s maximum output was 55.24 W, and its effective efficiency was 18.3%. In the next phase, we aim to complete a flexible, ultra-lightweight HAPS module weighing 500 – 550 g/m² by combining high-performance thin cells with further thinning of the encapsulation materials.

7. Perovskite/Silicon Tandem Solar Cells

Tandem solar cells that use perovskite as the top cell—such as perovskite/silicon, perovskite/CIS, and perovskite/perovskite two-terminal structures—are still under active development. However, some manufacturers have already begun mass production.

Currently, these tandem cells do not yet meet the cost, reliebility, and conversion efficiency required for HAPS applications. Nevertheless, their theoretical conversion efficiency exceeds 40%, and they can be manufactured using low-cost materials. These advantages have attracted significant global attention.

Since around 2017, research institutions and companies around the world have invested trillions of yen into development, triggering intense competition. Even as of 2025, new records in efficiency and reliability are being set almost every month.

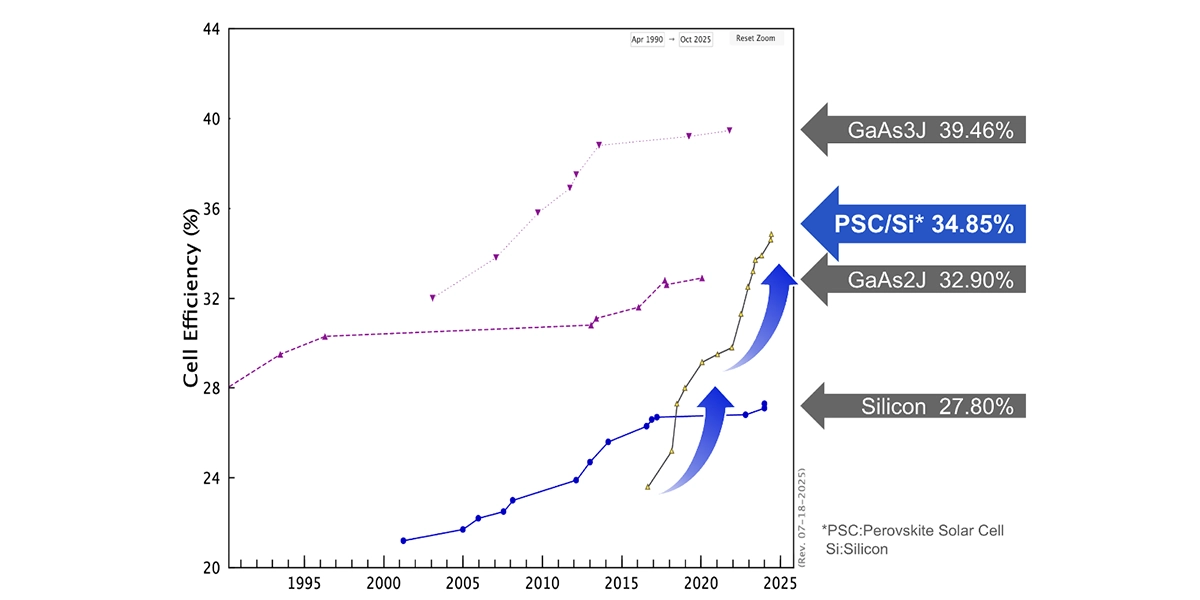

At the laboratory scale, small perovskite-based tandem cells have already surpassed GaAs 2-junction cells, achieving a conversion efficiency of 34.85% as of July 2025 (see Figure 9).

Figure 9. Best Research-Cell Efficiency Chart

Source:National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, operated by Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308.

Disclaimer– THE DATA ARE PROVIDED “AS-IS,” WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. DOE/NREL/ALLIANCE ARE NOT OBLIGATED TO PROVIDE SUPPORT OR UPDATES, AND USER ASSUMES ALL LIABILITIES.

The 34.85% efficiency of the perovskite/silicon tandem cell shown in this chart was recorded using a very small laboratory-scale cell (approximately 1 cm²) designed specifically to achieve maximum performance.

To make this technology for commercial use, it will be necessary to develop mass production techniques capable of consistently manufacturing larger cells, such as standards M6 to G12 (sized 16.6 to 21 cm square), and also improve cell reliability.

Notably, a world record of 33% efficiency has already been achieved for M6-sized tandem cells.

Based on this trajectory, it is expected that perovskite/silicon tandem cells with a 30% conversion efficiency suitable for ground-based practical applications will begin entering the market within a few years, with low costs as mass-production technology improves.

In its 2020 research, SoftBank analyzed the technological trends and forecasted that high-performance perovskite/silicon tandem cells would become available by the time HAPS is commercialized.

However, despite the extremely high theoretical potential of these next-generation cells, no validation data existed at the time for their operation in the stratosphere. Therefore, procurement and initial performance evaluation of actual cells were essential.

As of 2020, tandem cells were still in the lab-scale development stage, with only small-format cells being produced. They were not yet available in the commercial market, making procurement extremely difficult.

8. Tackling the Modularization of Perovskite/Silicon Tandem Solar Cells

In 2023 we successfully secured the first-ever supply of industrial size perovskite/silicon tandem cells in Japan. Additionally, we have initiated technical verification to rapidly apply tandem cells to ultra-lightweight laminates for HAPS. Initially, we attempted to repurpose the ultra-lightweight process developed for silicon, but perovskite is sensitive to both heat and moisture.

As a result, we had to adjust various factors such as humidity control in the cell placement area, environmental conditions during cell connection processes, and lamination temperature and time, gradually identifying optimal methods and accumulating know-how. Numerous challenges and improvement methods emerged on-site, and through a rigorous improvement cycle, we were able to develop the technology to lightweight modularize perovskite silicon tandem cells in a short period of time.

9. Can perovskite, which is highly susceptible to moisture, be protected using materials other than glass?

Perovskite is extremely vulnerable to moisture. If a cell is left exposed, the perovskite crystals absorb water vapor from the air like a desiccant. As a result, the cell can become unable to generate electricity within just a few weeks. In Japan, where the humidity often exceeds 50%, performance can critically degrade in only a few days. This weakness is the same for perovskite/silicon tandem cells. Therefore, sealing technology that completely blocks moisture and water vapor is essential.

In general, achieving a complete water vapor barrier requires the use of glass or metal. Since solar cells must transmit light, glass is effectively the only option. However, glass is heavy and inflexible, making it unsuitable for HAPS.

In satellites, solar panels are laminated with ultra-lightweight materials like ETFE. Other components use polyimide films layered with Al/SiO₂ to block ultraviolet and other radiation. Although this is a highly advanced technology, it offers little gas barrier performance, as there is no atmosphere in space.

In contrast, the stratosphere—HAPS operation place—still contains air. Therefore, while following a satellite-like approach of layering multiple functional coatings onto a resin substrate, it is also necessary to develop high-performance films. These films must offer strong gas barrier properties, flexibility even at around −70°C, and maintain the high optical transparency and UV resistance to avoid reducing power generation efficiency. The target thickness for these films is about 25 to 50 µm.

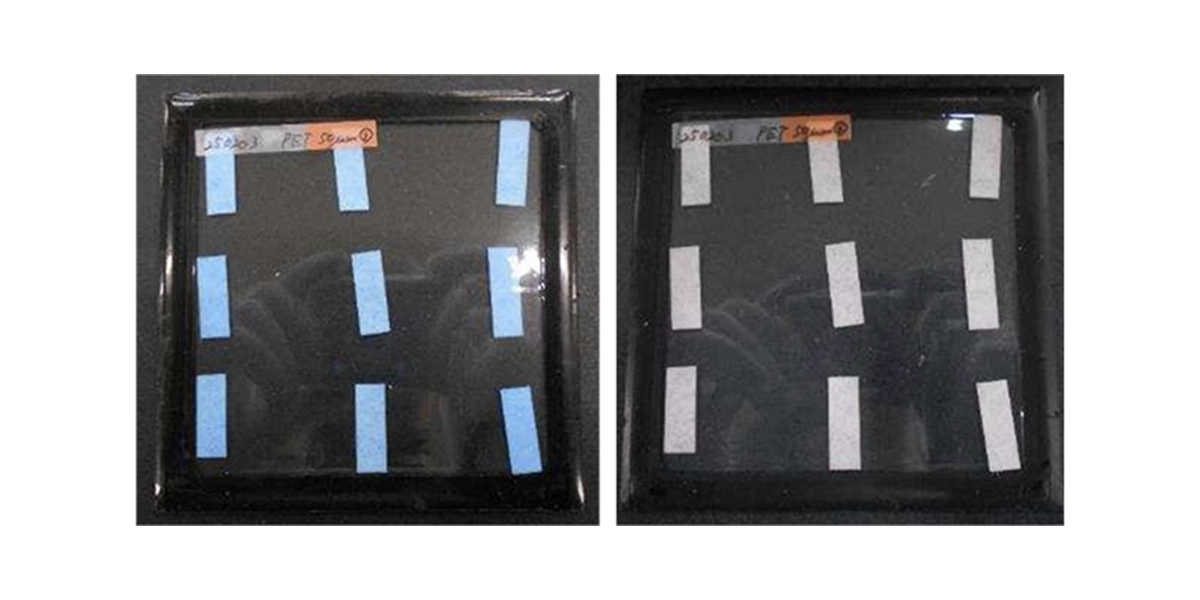

Figure 10. Normal PET film (before test→after 50h)

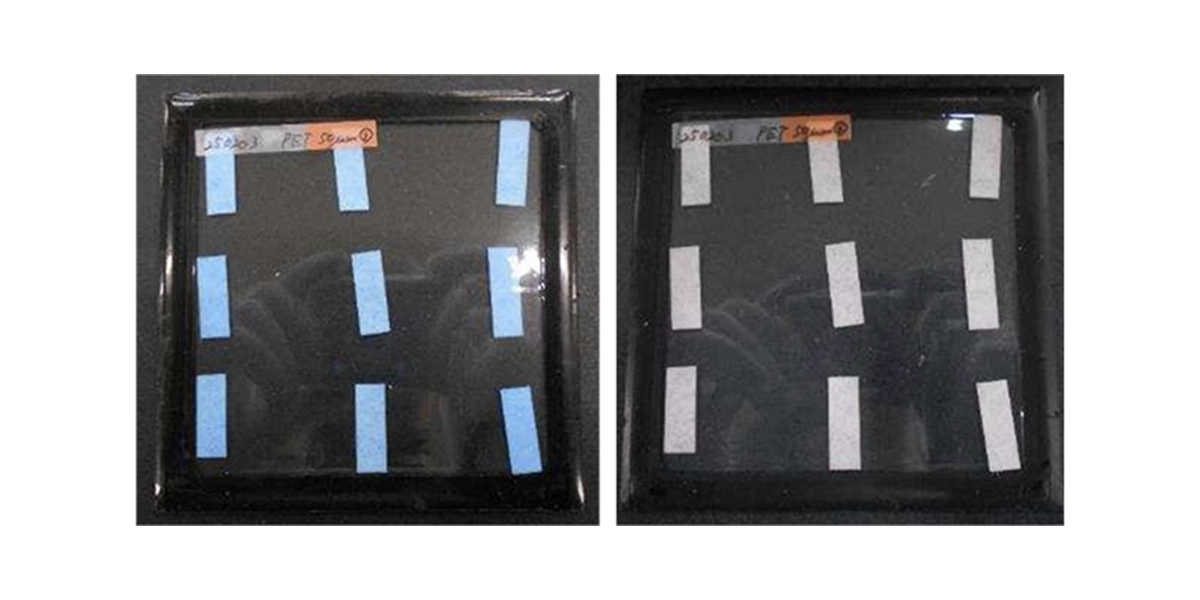

Figure 11. Barrier PET film (before test→after 100h)

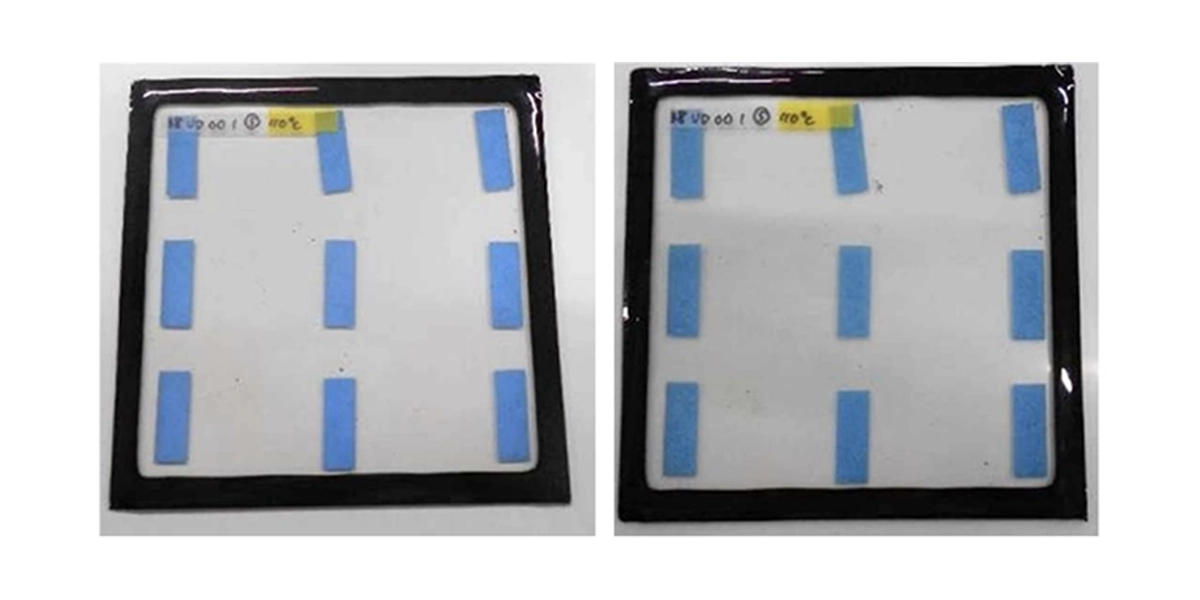

Figure 12. Barrier PET film (before testing → after 500 hours → after 750 hours → after 1000 hours)

As one example among many high-performance films and thin glass materials tested, Figures 10–12 show the results of a damp heat test comparing conventional PET and barrier PET. In this test, cobalt chloride paper was sealed inside the film, and the edges were completely sealed with butyl rubber to monitor the penetration of water vapor through the film surface.The cobalt chloride paper in the conventional PET sample turned completely white—indicating saturated moisture absorption—after 50 hours, demonstrating virtually no barrier performance (Figure 10).

In contrast, the barrier PET showed no discoloration even after 100 hours, confirming its ability to block water vapor (Figure 11). However, since its performance limit was unknown, an extended test up to 1,000 hours was conducted. The barrier PET began to show discoloration after approximately 500 hours.

Compared to conventional PET, which reached full saturation at 50 hours, barrier PET did not reach saturation even after 500 hours, confirming that it has at least 10 times higher gas barrier performance.

Moreover, the optical transmittance of the barrier PET remained above 90% even after 1,000 hours, and no significant power loss was observed within this test duration. These results indicate that barrier PET is a strong candidate for protecting perovskite cells from moisture.

The next challenge is that PET tends to yellow when exposed to prolonged UV radiation.

In the stratosphere, where UV intensity is about 1.5 times stronger than at ground level, PET is expected to yellow more quickly, which may obstruct sunlight and reduce power output.

To use barrier PET in the stratosphere, one option is to add UV-absorbing functionality, though this would increase thickness and weight. Alternatively, if cost allows, a practical approach might be to simply replace the module when yellowing becomes significant. In any case, to be used for HAPS solar cells, the material must satisfy all these technical requirements.

10. Practical application of ultra-lightweight tandem modules and expansion plan for HAPS

Going forward, our plan is to secure the latest thin-film cells, reduce the thickness of both encapsulation material and tabs, and target a module weight of 500 g/m².

At the same time, we will work to integrate and optimize the ultra-lightweight lamination process with the specific pretreatment and low-temperature lamination requirements unique to perovskite tandem cells.

In parallel, we will introduce a large-scale testing facility in Japan that can simultaneously replicate low temperature, low pressure, strong UV radiation, and ozone exposure—conditions characteristic of the stratosphere.

Using this facility, we will apply stress to protective films, encapsulation materials, and assembled solar modules under near-real environmental conditions, in order to evaluate materials and determine optimal configurations.

By integrating these developments, SoftBank, together with its partner companies, aims to build a robust and scalable supply chain for mass-producible, cutting-edge, ultra-lightweight, high-efficiency tandem modules for HAPS, enabling the stable and cost-effective delivery of optimized devices for future HAPS operations.