- Blog

- Wireless, HAPS

【Part 1】What Is the New Optical Communication Technology for Space and the Stratosphere? A Beginner-Friendly Introduction

#HAPS #OpticalWirelessCommunication

Oct 16, 2025

SoftBank Corp.

Topics

1. From Hertz to Photons: The Evolution of Communication

Looking back at human history, communication has taken many forms: carrier pigeons, written messages, bells, gongs, smoke signals, and reflected light from mirrors. After the invention of electricity in the 19th century, wired telegraphy and telephone communication became mainstream. Meanwhile, on the open seas where wires could not be connected, optical Morse code and semaphore were dominant until wireless communication was finally put into practical use in the early 20th century. Since then, the expansion of the radio spectrum as electromagnetic waves has continued for about 100 years—extending in frequency from short waves to millimeter waves and terahertz, and spatially from underwater to geostationary satellites. However, the more accessible frequency bands have already been used up, and resources available for communication are reaching their limits.

Optical communication has the potential to surpass this. Within the range covered by wired optical fiber, internet services of up to 10 Gbps have become available to households, and progress continues toward optoelectronic integration, where optical signals directly enter and exit chipsets in network equipment. On the other hand, similar to wired communications in the 19th century, optical signals have yet to reach mobile and rural areas. Unlike radio waves, light has difficulty traveling through rain and moisture in the atmosphere, and there are limits to ground-based point-to-point communication. Going forward, enabling optical communication even in areas without optical fiber as a key technology for NTN (Non-Terrestrial Networks) is a major challenge for communication companies.

2. Beyond the Fiber: Pioneering Free-Space Optical Frontiers

Light is also a type of electromagnetic wave, so obtaining a transmission light source, modulating it, and sending information does not fundamentally change. When semiconductor lasers became practical in the 1970s, they were used for reading DVDs, and once their power was increased, they became applicable for long-distance optical communication. Long-distance optical communication lasers are monochromatic and phase-coherent. For example, while a microwave of 20 GHz has a wavelength of 1.5 cm, a laser used for optical communication typically has a wavelength of about 1.55 μm (chosen because optical amplifiers are easier to make), which is 1/10,000 that length. In submarine cables and urban long-haul optical fiber, this laser light is connected to a single-mode fiber of about 10 microns, enabling long-distance, low-loss transmission. Connectors are carefully designed to align fiber axes, and as long as operators avoid dust and dirt, a fiber only one-tenth the thickness of a human hair can be precisely coupled to enable communication at both ends.

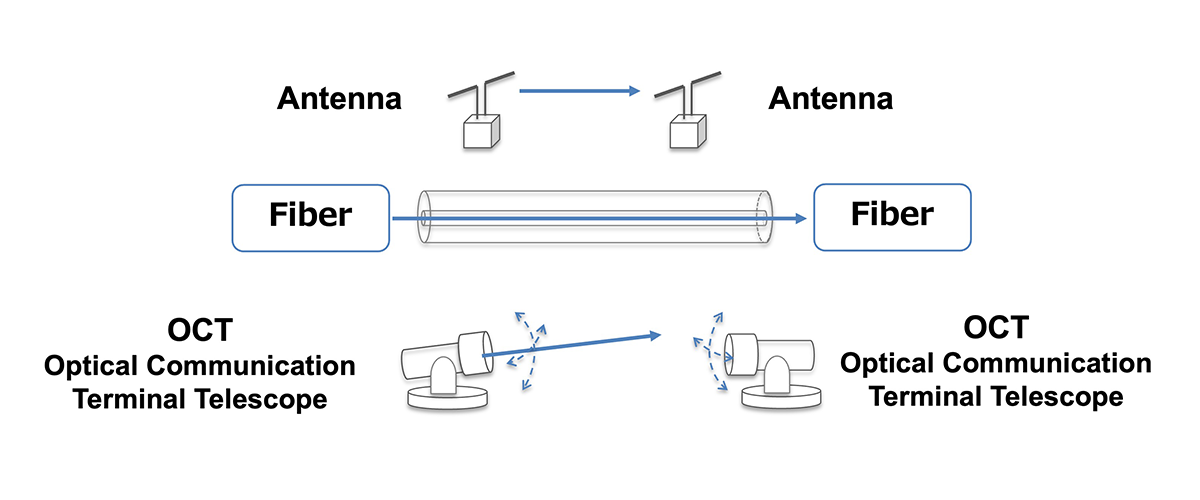

In contrast, free-space optical communication requires acrobatic techniques: based on positional information of both ends, the receiving side must capture the counterpart’s communication light, establish a link, and guide the captured light into a fiber while maintaining lock. Moreover, since the wavelength of 1.5 μm is in the infrared range, it is invisible to the human eye.

On the ground, systems like Taara exist to connect the "last mile" with light between buildings or across distances, but such equipment has not yet become widely used. Furthermore, when the communication terminals are mounted on moving platforms such as aircraft or satellites, gimbals are required for large-angle control and tracking in azimuth and elevation. Thus, the establishment of free-space optical communication hinges on a fusion of optics and mechatronics. Due to its high directivity, unlike radio waves, it is free from interference and spectrum coordination issues.

Figure 1. Communicating with Light: Where Precision Alignment Replaces Broad Coverage

3. How Optical Wireless Communication: The IMDD Approach

Next is modulation in free-space optical communication. How is information placed on light? The basic method is intensity modulation, IMDD (Intensity Modulation / Direct Detection), which represents 1s and 0s by turning light on and off. On the transmitting side, light intensity itself is switched ON and OFF to send data, and on the receiving side, the incoming photons are detected by a diode to determine 1 or 0. More advanced methods use the phase of light, such as coherent modulation, which is employed in optical fiber networks. Coherent methods with QPSK and other advanced modulation schemes can send large amounts of data, but they require large circuits. Since satellite links involve significant Doppler shifts, IMDD is the starting point.

Similar to how control signals initiate radio communications, optical communications also have preparatory stages:

(1) Two optical communication terminals in space or the stratosphere use GNSS data to predict each other’s azimuth and elevation, broaden guide beams, and perform initial acquisition (coarse tracking).

(2)The receiving terminal uses quadrant tracking sensors to continuously control beam direction and guide the light into a fiber.

(3)Finally, the optical signal is input to a photon detector, and decoding is performed.

For example, with a 1 W laser at 1.55 μm communicating with a satellite 1,000 km away, the beam spread at the satellite would be about 100 m in diameter. If the satellite uses a 10 cm telescope at 10 Gbit/s, hundreds of photons per bit can be received. Since achieving a BER (bit error rate) of 10^-6 requires several tens of photons per mark, a reliable link is possible. While this calculation is similar to field strength estimation in radio, in practice, losses and background noise must be considered, and sufficient design margins are applied.

Figure 2. The basic structure of an optical communication system consists of receiving the transmitted light and guiding it into an optical fiber.

4. Previous Achievements in Satellite-to-Satellite Optical

Here are some milestones in free-space optical communication:

・Nov 30, 2001 — SILEX: SPOT-4 (LEO) ⇄ ARTEMIS (GEO)

First-ever satellite-to-satellite laser image transmission. About 50 Mb/s using 800 nm semiconductor lasers.

・Dec 9, 2005 — OICETS ("Kirari") ⇄ ARTEMIS

JAXA and ESA succeeded in two-way optical inter-satellite communication (LEO–GEO). Announced as “the world’s first bidirectional” success.

https://global.jaxa.jp/projects/sat/oicets/

・2007 — NFIRE (US MDA) ⇄ TerraSAR-X (Germany, DLR)

Continued demonstrations of LEO–LEO links using TESAT’s LCT. Later announced as “the first stable in-orbit laser link.”

・2013–2014 — Alphasat (GEO, TDP#1 LCT)

Precursor to Europe’s EDRS optical relay network. Demonstrated up to 1.8 Gb/s with links of ~45,000 km.

・Jun 1, 2016 — EDRS-A (GEO) ⇄ Sentinel-1A (LEO)

First operational image transfer via laser in Europe’s SpaceDataHighway. Achieved 600 Mb/s, with terminals capable of 1.8 Gb/s.

・2021 launch → Dec 5, 2023 — ISS (ILLUMA-T, LEO) ⇄ LCRD (GEO)

NASA achieved the first ISS–GEO laser relay link (1.2 Gb/s downlink, 155 Mb/s uplink).

・Aug 2024 → Jan 2025 announcement — ALOS-4 "Daichi-4" (LEO) ⇄ JAXA LUCAS (GEO)

First successful relay of observation data via 1.5 μm-band LEO–GEO optical link. Announced as the world’s first mission data transmission in this band.

https://www.jaxa.jp/press/2024/10/20241008-1_j.html

・2021 onward — Starlink (LEO megaconstellation)

Large-scale implementation of laser ISLs. In 2024, SpaceX announced plans to sell terminals externally.

・Jan 2025 — SDA (US Space Development Agency)

Demonstrated cross-manufacturer ISL links between York Space Systems and SpaceX satellites, compliant with SDA’s OCT standard.

Starlink is particularly notable, as it is already implementing practical LEO-to-LEO free-space optical networks (NTN). Beginning around 2020, mass deployment began in 2021, with each satellite carrying around four laser ISL terminals. This enabled multi-Gbps communication over hundreds to thousands of kilometers, providing service in regions with few ground stations, such as oceans and polar areas. SDA’s cross-vendor interoperability is also a significant step.

While Japan lags 3–4 years behind in LEO-to-LEO NTN optical communications compared to other nations, its long-standing expertise in satellite and optical technologies provides ample opportunity to catch up—just as Japan did with radio in the early 20th century. SoftBank is determined to accelerate Japan’s contribution with a similar pioneering spirit.

5. Steps Toward HAPS–Satellite Optical Connectivity

The small-satellite optical communication terminal now under development marks a major step in applying NICT’s long-standing optical communication technologies. Combining Kiyohara Optics’ optical expertise, modem manufacturing techniques, and ArkEdge Space’s satellite integration capabilities, a highly integrated 6U satellite was realized in a short time. Although this satellite only demonstrates basic optical communication functions (without transmitting real image data from cameras), it can confirm data rates by sending specific bit patterns and receive optical data from the ground. This will be a valuable breakthrough for future small satellites, which face limited radio frequency spectrum.

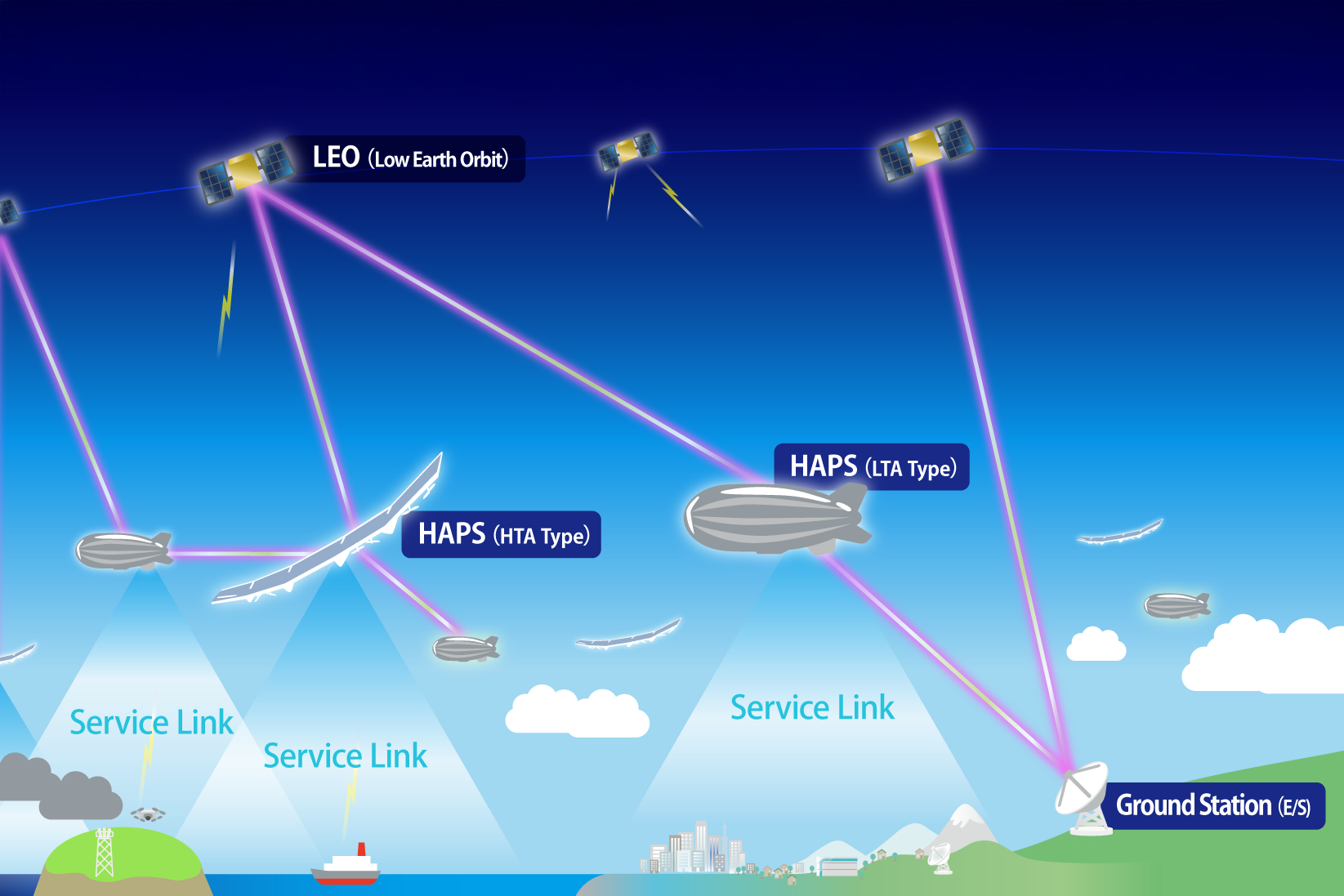

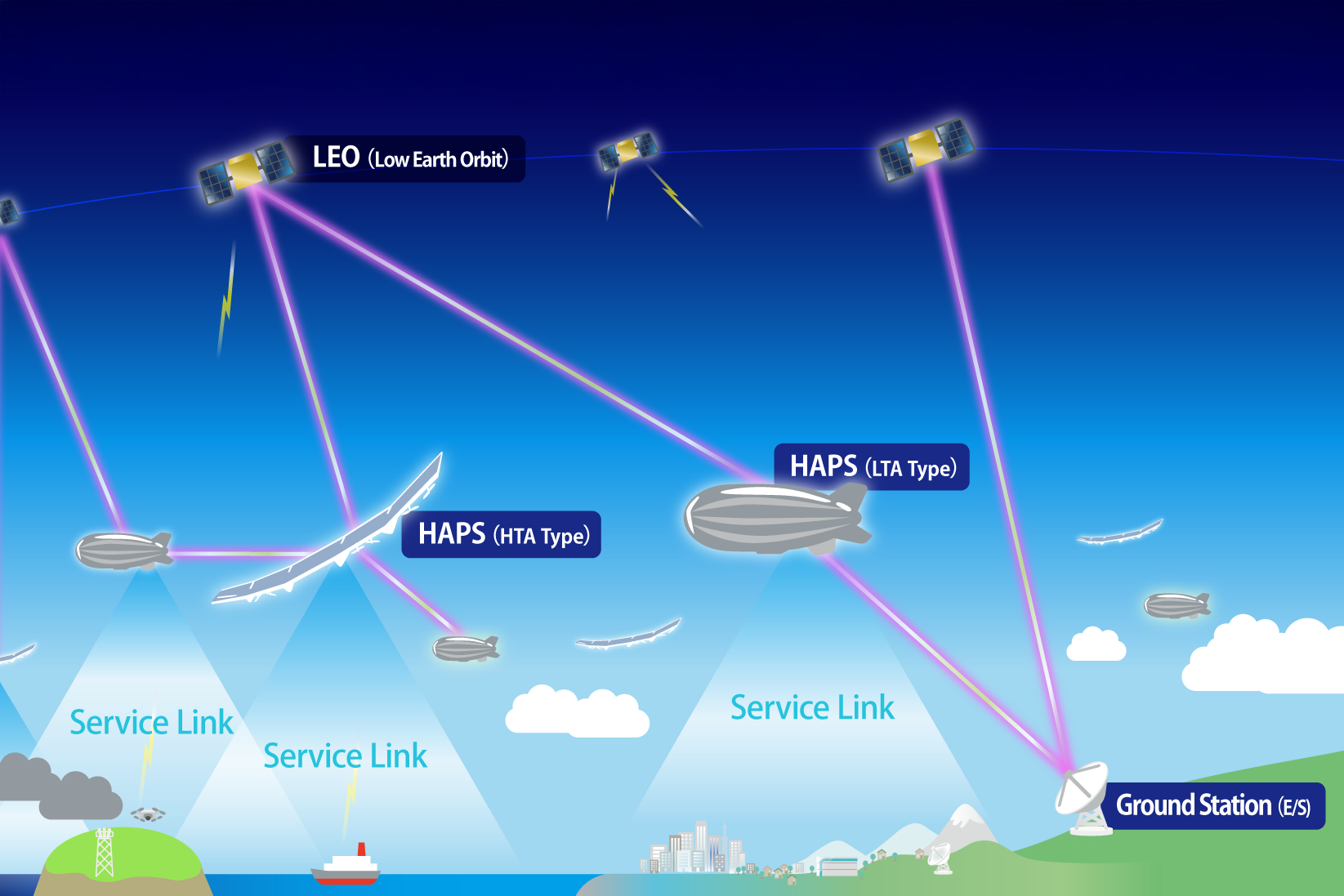

Meanwhile, SoftBank is developing HAPS-mounted optical communication systems to outpace overseas NTN operators. The stratosphere is severe than space, with environments reaching varying -90°C, limited bus power availability, and stability differences between HTA (aircraft-type) and LTA (balloon-type) platforms. Optical terminals and gimbals must be designed accordingly.

In cellular communications, hierarchical cell sizes greatly improve network performance. Since LEO satellites cover very large cells, efficiency in dense populated areas is reduced. The HAPS layer can improve accommodation efficiency, enhance service performance, and optimize ground gateway connections. More details will be introduced in a blog post that is scheduled to be published in January 2026.

Starting with one small satellite and conducting optical communication demonstrations between HAPS and LEO satellites, SoftBank aims to showcase the potential of adding a new HAPS layer to NTN, opening a new perspective for next-generation networks.

Figure 4. A new framework is driving the development of a Japan-made optical communication terminal for NTN.