In this day and age, we benefit from a multitude of Internet-based services, and the sharing economy, or XaaS—an abbreviation for ‘X (anything) as a Service’—in particular is getting a lot of attention recently.

Among XaaS offerings, ride sharing and bicycle sharing are well known to consumers. Recently, however, a new wave of sharing economy services have appeared, with offerings related to clothing, housing, knowledge, skills, and even umbrellas.

The XaaS concept of renting goods in favor of owning them is not entirely new, however. Long before the dawn of the Internet, sharing economy services existed in Japan’s Edo period (1603-1868).

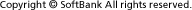

Masumi Horiguchi, a popular authority on the period, talked to Hiroaki Ichikawa, a curator at the Edo-Tokyo Museum to find similarities in Edo period and modern Japan lifestyles.

Table of Contents

- Sharing culture rooted in lack of property and possessions

- The legacy of the Edo period’s sharing culture

- What is trash now was treasure in the Edo period

Meet the guides

Masumi Horiguchi (Edo personality)

A native of Tokyo’s Adachi Ward, Horiguchi has been interested in history since elementary school. At college she studied Kabuki and Japanese culture while also training in theatre, Japanese dance and swordplay. After graduation, she was the youngest person ever to be accredited with Edo Cultural History Certification Level 1. Since then she has gained popular recognition for introducing Edo period history to a wider audience through TV and radio appearances, books, events and lectures.

Hiroaki Ichikawa (Urban history research chief and curator, Edo-Tokyo Museum)

Born in 1964 in Aichi Prefecture, Ichikawa is a graduate of the Graduate School of Social Sciences at Hitotsubashi University. He specializes in modern urban Japanese history and has edited various publications, including books that survey studying and recycling in the Edo period.

Sharing culture rooted in lack of property and possessions

The Edo-Tokyo Museum’s restored Nihonbashi Bridge greets visitors as they enter the exhibition space

In modern Japan the sharing economy is a buzzword that refers to Internet-based shared services for just about anything, including clothes, umbrellas, events, work spaces, movies, books and daily necessities. In the Edo period, though, among the commoners there was a culture of sharing things.

Yes. For example, the Edo term sonryo or “rental charge” is still alive in modern Japanese. This refers to a business model where clothes and utensils were rented out and consumption costs were collected as a rental fee. This business style is known to have originated in the Edo period. In other words, sonryo can be seen as the origin of Japan’s modern rental services.

Since all of these things were related to daily life, in XaaS terms we could probably classify sonryo as “LaaS” or “Life as a Service.” So, what types of rental items were prevalent?

The most well-known rental item was the futon. After that, summer and winter kimono and mosquito nets were also well-used items. These rental items were seasonal; mosquito nets were only available in the summer and there were futons for both summer-use and winter-use. When the season changed, people would refinance and return their unused items. However, unlike now, rental services were not available for a wide range of goods.

And that style of business was established because commoners then faced various life challenges unique to their time.

In a modern society, almost everything has a market, but that wasn’t necessarily the case during the Edo period. However, it’s thought that the practice of sharing became somewhat rationalized economically. The sonryo business was born from the concept of “if you buy something, you need to store it somewhere; but if you don’t have the space to store it, it’s better to rent the item only for when you need it.”

It seems the tenement houses where the Edo period commoners lived were very small. There’s a full-sized tenement house diorama at the Edo-Tokyo Museum and one can really get the feeling of how small those spaces were.

People didn’t keep possessions due to frequent fires

Residents of many different occupations lived together cooperatively in tenements

This photo shows a small room in a rear tenement (about 2.7 meters wide and 3.6 meters long). Except for shared facilities like the bath and toilet, people lived their lives in this type of space. Moreover, not only were the rooms for Edo period commoners small, there were also a lot of fires at that time, so they didn’t really keep personal property. Or more precisely, they led lives where they were unable to keep their own possessions.

One could say that Edo era people were just living day-to-day. People were only able to really make a living for the day by using the money they earned that same day, without a thought for the future. It’s often said that true Tokyoites are liberal with their money, as in the Japanese saying, “having no money for an overnight stay.” This is generally understood to convey the good-natured character of born-and-bred Tokyoites, but in reality, the phrase refers to the fact that the earnings of the Edo era workforce were completely used up by life’s daily activities, leaving no surplus whatsoever.

The legacy of the Edo Period’s sharing culture

Nihonbashi’s Echigoya Dried Goods Store was said to have a rental service for oilpaper umbrellas

I’ve heard that rental stores even offered fundoshi (a traditional Japanese loincloth undergarment). Is that true?

From the end of the Taisho era (1912-1925) to the beginning of the Showa era (1926-1989), publications looking back on the Edo period became popular, including a magazine called Comet. There was a record in that publication that during the Bunkyu period (1861-1864, the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate) an old man bought a fundoshi for 248 mon (the currency at the time), used it and then paid 60 mon and received a new one. I’m not certain if this was a “rental fee” or a “laundry fee,” but it’s likely that it’s this particular story that spread.

1 mon would be worth about 20 yen today, so 60 mon is about 1,200 yen in modern day terms! That’s fairly expensive, isn’t it?

Assuming a new fundoshi was about 248 mon (about 5,000 yen) then guessing whether it was a rental fee or a laundry fee, 60 mon seems unlikely. So, I think this tale is a bit dubious.

A new fundoshi was really expensive!

It’s true that cloth back then was expensive, unlike now. However, since a fundoshi was not a seasonal item, I guess rental stores didn’t deal with them. Well, how about we move on to the next topic (laughs).

Different styles of sharing: from the basket maker to the boathouse, gambling, the well, and more

Recreation of a terakoya (temple school)

In modern Tokyo there are many services on offer that share “space,” such as WeWork and share houses. It’s a field that can be called “WaaS” (Workplace as a Service) and in the Edo period I think public bathhouses could also fall into this category. What do you think? On the second floor of bathhouses there were entertainment halls.

I think we could classify them as WaaS. As you know, because there were no indoor baths in the homes of common people during the Edo period, people often went to public baths and the men were able to go upstairs and pay to use the rest area. It was typical in the sense of being a community meeting place where people could gather on a daily basis.

XaaS terms learned from the Edo period: WaaS (Workspace as a Service)

WaaS refers to spaces created to implement a variety of new working styles like mobile-first and remote work. The SoftBank Group invested in the community-based coworking space provider WeWork.

Ride sharing is popular these days and could be called “MaaS” (Mobility as a Service) or “TaaS” (Travel as a Service). Were there examples like this in the Edo period?

There were kago (a type of palanquin) and there were also boathouses where people could share the use of boats for recreation or for the transportation of goods.

XaaS terms learned from the Edo period: MaaS (Mobility as a Service)

MaaS refers to shared transportation services, including public transport, that support business and daily life. SoftBank Corp. (TOKYO: 9434), through MONET Technologies, a joint venture with Toyota Motor Corporation and other companies, is working to popularize MaaS in anticipation of the coming era of autonomous driving technology.

A replica of a kago (a type of palanquin) used by lords during the Edo period

“PaaS” (Payments as a Service) has also gone mainstream. Of course, this refers to cashless services such as the smartphone payment service PayPay. In the Edo period, people pooled their savings together and went on trips if they won a lottery. People also liked to travel in groups known as ko to worship at Ise Shrine or Mount Fuji.

At that time, mountain worship was very popular and it’s said that it was practiced not only in cities but also in villages. However, it seems that the term ko, which was used by these worship groups, was also used by samurai to disguise the fact that they were gathering not to worship but to take part in illegal activities like gambling.

XaaS terms learned from the Edo period: PaaS (Payments as a Service)

The exchange of money on the cloud, rather than by using physical cash, has been increasing rapidly. The smartphone settlement application PayPay provided by companies in the SoftBank Group is a form of PaaS.

A dashi (festival float) used at the Kanda Festival. Festivals were sometimes funded by local residents

This isn’t related to Edo, but was this kind of sharing also happening in rural villages?

Actually, sharing would have been even more necessary in rural areas. You can’t manage fields and irrigation or re-thatch a roof on your own. People had to help each other in order to maintain their living standards, so they didn’t have sharing services in the commercial sense.

Community wells were used as places to socialize. The Japanese word for idle gossip literally means “meeting at the edge of a well”

They didn’t have sharing services for agriculture, so I don’t think the term “AaaS” (Agriculture as a Service) is appropriate, but we could say the spirit of mutual assistance was more prevalent in the Edo period than it is today.

True. But on the other hand, compared to rural villages, Edo was quite special. As a big city, there would have been a lot of strangers around. These sharing-economy businesses were established for large numbers of people that just wouldn’t have been imaginable in rural communities.

XaaS terms learned from the Edo period: AaaS (Agriculture as a Service)

Services are expanding in primary industries where capital investment is expensive. Particularly in agriculture, the idea of “smart farming” is gaining traction and initiatives such as production management utilizing technology, labor saving methods and knowledge sharing are underway.

SoftBank Corp. provides the agricultural AI brain “e-kakashi,” a solution that analyzes data gathered from the field based on plant science and assists with cultivation decisions.

Businesses resembling modern day fast food, some selling sushi, began to appear in the Edo period

What is trash now was treasure in the Edo period

It’s surprising that people in the Edo period already understood the value of sharing and letting go of useless things, even though they didn’t have an understanding of modern economics. Many young people came from other regions to Edo for seasonal work, so they needed to stay close with other people during this time. People didn’t have a lot of money and the economy itself had very low growth. Yet, people were somehow able to get by in what was known as a “recycling society.” The structure of society as a whole was different from ours, but I feel that there was a lot in common with modern Japanese young people’s feelings of frustration in not being able to get ahead.

That’s right. If we analyzed the real economy of the Edo period there might have been growth, but people would not have been aware of this economic progress at all. It was a zero-sum game where the total amount of wealth was fixed and if someone gained, someone else lost. Because of this, I think high interest loans were despised, and this rational economy mentality came from a desire to get rid of excess and rent goods when possible.

So, it’s different from our modern values of “sharing is wonderful” and “minimizing possessions is good for the environment.” I thought it might be interesting to find some hints from the economic sensibilities of Edo period people that might be useful for us now.

We can definitely learn something from Edo, but I think the point is a little different. People often talk about the Edo period as having a recycling culture and through learning about that tradition we ourselves should continue to recycle. However, in actuality, sewage was not something useless but rather something of value as a commodity then. Modern people feel that something like this has no value or that it’s trash, but for Edo people it was just a normal part of the economic cycle.

Our ecology is a bit different from the Edo period, too, because now it’s essentially about how to recycle things that don’t have market value and how to reduce emissions. However, the spirit of cherishing things or of cleaning up after yourself is still very important, so I think in that sense we can definitely learn something from people then.

And the Edo-Tokyo Museum was created to convey those lessons, right?

The type of work I do helps people see Edo society as the roots of our modern society. So it makes people feel the humanity of that period.

Viewing modern Japan through the lens of the Edo period

The terms XaaS or sharing economy might be unfamiliar to some, but in plain terms it means information or a process that allows everyone to share and use one resource efficiently. In that sense, the sharing spirit of the Edo people still lives on today in Japan, where people can rent daily necessities, like bedding, or when they chat at local bathhouses.

Though the Edo period seems to be a completely different time, there are many parallels with the modern era. Looking back to the past can actually help people better understand modern concepts like XaaS.

(Original article posted on February 20, 2020)

Text by Ryo Kurihara

Photos by Munenori Nakamura

Special thanks to the Edo-Tokyo Museum